Multitasking: Definition, Examples, & ResearchWhat is multitasking, and can research tell us whether it’s good or bad? Read on to find out everything you need to know about multitasking.

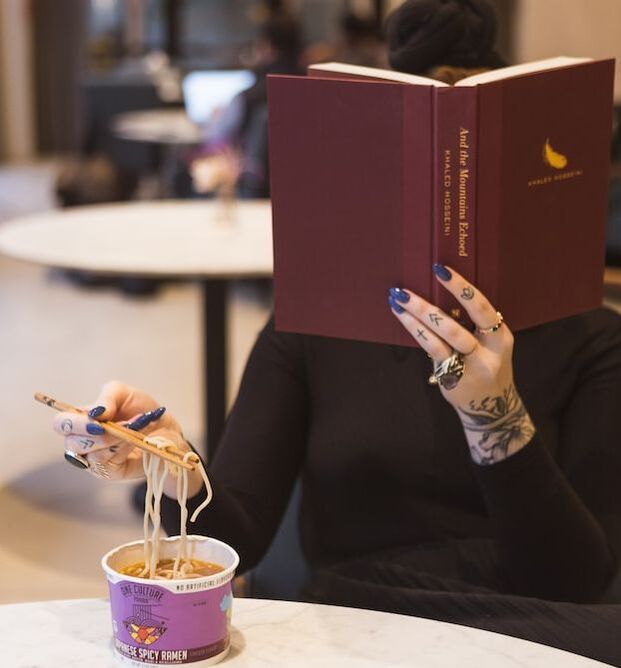

This debate centers around an age-old question of attention, namely, can we truly give our attention to more than one thing at a time? And if we can, is that a good thing or a bad thing? This article will define multitasking – the most important example of divided attention I can think of – and try to answer our burning questions about whether dividing our attention is good, bad, or somewhere in between.

Before reading on, if you're a therapist, coach, or wellness entrepreneur, be sure to grab our free Wellness Business Growth eBook to get expert tips and free resources that will help you grow your business exponentially. Are You a Therapist, Coach, or Wellness Entrepreneur?

Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to

|

Are You a Therapist, Coach, or Wellness Entrepreneur?

Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to Grow Your Wellness Business Fast!

|

Terms, Privacy & Affiliate Disclosure | Contact | FAQs

* The Berkeley Well-Being Institute. LLC is not affiliated with UC Berkeley.

Copyright © 2024, The Berkeley Well-Being Institute, LLC

* The Berkeley Well-Being Institute. LLC is not affiliated with UC Berkeley.

Copyright © 2024, The Berkeley Well-Being Institute, LLC