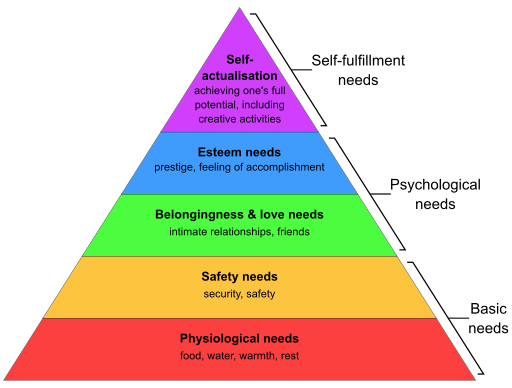

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Definition, Examples & ExplanationMaslow’s hierarchy of needs describes why we pursue one of our needs over another. Read on to see the uses - and limitations - of this fundamental psychology theory.

As you read this article, you will learn all about how scholars have applied Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to understanding our lives – and get a chance to think about your own motivations and priorities.

Before reading on, if you're a therapist, coach, or wellness entrepreneur, be sure to grab our free Wellness Business Growth eBook to get expert tips and free resources that will help you grow your business exponentially. Are You a Therapist, Coach, or Wellness Entrepreneur?

Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to

|

Are You a Therapist, Coach, or Wellness Entrepreneur?

Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to Grow Your Wellness Business Fast!

|

Terms, Privacy & Affiliate Disclosure | Contact | FAQs

* The Berkeley Well-Being Institute. LLC is not affiliated with UC Berkeley.

Copyright © 2024, The Berkeley Well-Being Institute, LLC

* The Berkeley Well-Being Institute. LLC is not affiliated with UC Berkeley.

Copyright © 2024, The Berkeley Well-Being Institute, LLC